Gender-affirming hysterectomy

Who is this information for?

This information relates to planned gender-affirming hysterectomy as a standalone

procedure (ie it is not being undertaken at the same time as phalloplasty, metoidioplasty or other bottom surgeries). It should be noted that you may still have these surgeries separately after a standalone hysterectomy. This information is intended for trans men, non-binary and intersex people who have decided on hysterectomy (with or without removal of the fallopian tubes and ovaries) after discussion with their gender specialist and surgeon.

This leaflet uses “hysterectomy” generally to describe all procedures including removing the womb or uterus with or without removal of the ovaries and fallopian tubes. More information on these choices is found below.

Content warning: This document uses some anatomy/biological terms where it’s important to be precise.

Gender-affirming hysterectomy

You may have many reasons for choosing hysterectomy. Some may not be related to your transition. Some people have severe pelvic pain that medicines or hormone treatments have not fixed. Others have profound post-orgasm bleeding or pain. The same medical reasons for performing hysterectomy for a cis woman can also apply to anyone else with a womb. It is important to talk through your reasons with your gender specialist and surgeon.

Hysterectomy operations offered at Chelsea and Westminster

We offer laparoscopic surgery (a minimally invasive keyhole approach) for almost all patients having gender-affirming hysterectomy. You’ll have either a robotic-assisted or a laparoscopic hysterectomy or sometimes a vaginal hysterectomy.

With the robotic or laparoscopic types of hysterectomies, your surgeon will make several small incisions (surgical cuts) on your abdomen. They’ll put a laparoscope (a long, thin surgical tool with a video camera) through one of the incisions into your abdomen. The laparoscope lets your surgeon see the inside of your abdomen.

Carbon dioxide gas will be pumped into your abdomen to make space. This gives your surgeon more room to do your surgery. Your surgeon will also put long, skinny surgical tools into the other incisions on your abdomen.

- With a laparoscopic hysterectomy, your surgeon directly controls the surgical tools with their hands. They can see the images from the laparoscope on a television monitor.

- With a robotic-assisted hysterectomy, your surgeon sits at a console and controls a robot that moves the surgical tools. The console has a special monitor where they can see the images from the laparoscope on a high-definition 3D screen.

With both types of hysterectomy, your surgeon will remove your uterus, cervix and fallopian tubes through your front-hole, if possible. If you have decided on having one or both ovaries removed, your surgeon will also remove these. If your uterus or cervix (+/- ovaries) can’t be removed through your front-hole (for example if your uterus is enlarged by fibroids or you have a big ovarian cyst), your surgeon will make one of your abdominal incisions bigger and remove your uterus and cervix from there. This is uncommon. Then they’ll close your incisions with sutures (stitches). If you’re planning bottom surgery, it’s important your surgeon knows which bottom surgery you’re considering so that they can use an appropriate abdominal

incision in the unlikely event that open surgery is required.

What are the risks of surgery?

Robotic-assisted and laparoscopic hysterectomy are safe procedures, and we have a low complication rate, but they remain major surgeries. Any surgery has the risk of complications, and rarely these complications can be very serious. It’s important you understand these risks before you consent to surgery.

Immediate risks—during or shortly after surgery

Less common—fewer than 1 in 20:

- Conversion to subtotal hysterectomy (this is rare in our practice)

- Change from keyhole to open surgery if there are unexpected complications or the uterus is very large

- Significant bleeding requiring blood transfusion

Rare—fewer than 1 in 100:

- Compression injury to nerves around where we operate

- Damage to surrounding structures (like bowel, bladder, the ureters or blood vessels)

- Failure to complete procedure

- Perioperative risks of the anaesthetic and other medicines

Early risks—in the days after surgery

Common—more than 1 in 20:

- Abdominal and shoulder tip discomfort due to trapped gas

- Ileus (sluggish bowels)

- Pelvic infection requiring antibiotics

- Vaginal bleeding

- Wound complications

Less common—fewer than 1 in 20:

- Urinary retention (difficulty passing urine such that we need to place a urine catheter into your bladder for a short period of time)

Rare—fewer than 1 in 100:

- Blood clots (deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolus)

- Vaginal vault dehiscence (where the top of the front-hole comes open if the stitches fail. Sometimes this requires repair under general anaesthetic.)

- Need to go back into theatre

- Pelvic abscess, a 1 in 500 chance

- Vaginal vault haematoma (collection of blood at the top of the front-hole)

- Death, a 1 in 3,000 chance

Late risks—in the months or years after surgery

Common—more than 1 in 20:

- Infertility (if the uterus is removed, you will not be able to get pregnant. If both ovaries are removed, you will not subsequently be able to use your own eggs in assisted conception to have a baby unless you have previously undergone egg retrieval)

- Dyspareunia (discomfort during front-hole sex)

- Premature ovarian insufficiency/menopause symptoms (this is uncommon for patients taking long term testosterone but there is little evidence on long-term outcomes)

- Symptomatic abdominal adhesions

Less common—fewer than 1 in 20:

- Hernia from a keyhole cut (port-site)

- Regret (the feeling of regretting having had gender affirming hysterectomy is poorly understood in the medical literature)

- Front-hole vault prolapse (where the top of the front-hole prolapses down into the front-hole, sometimes bulging out)

What to expect

On the day of surgery

Most people are admitted to hospital on the day of their surgery and are discharged the same evening or the next morning. You will be admitted to an all-gender mixed-specialty surgical admissions area on the day of your operation and seen by the nurse. Your vital signs will be measured, and the nurse will run through a checklist of questions. Your surgeon or a member of their team will see you and go through the consent form you signed electronically. Ask any questions you have about your surgery, as we want you to be fully informed and involved in

your care.

Depending on the order of the day’s operations, you may have to wait for a few hours to be brought to the operating theatre to start your surgery, so bring a book or iPad with you to keep you occupied. Free NHS WiFi is available throughout the Trust premises.

After surgery

You will wake up initially after surgery has finished in the Recovery Room where a nurse will monitor you closely until you are fit to go back to the ward. You’ll go back to a male ward with single gender (male) shared bathrooms, or private en-suite facilities. If you would prefer to be accommodated after your operation on our dedicated female-only gynaecology ward, Annie Zunz, please let your surgeon know if this is the case during your first consultation or let the surgical scheduler know when you agree your date for surgery.

You may have a catheter (tube) in your bladder to allow drainage of your urine if your surgery is performed in the afternoon or your surgery took longer than average. This is usually removed the morning after surgery by a trained member of clinical staff familiar with transmasculine patients when you are easily able to walk to the toilet to empty your bladder. If you have problems passing urine, you may need to have a catheter for a few days to let the bladder rest before the catheter can be removed; this is uncommon.

If you’ve had a catheter inserted, you’ll probably stay overnight after your surgery. After your catheter is removed the morning after surgery, it’s important to move around early on to help your recovery. Start by sitting up in bed and moving around on the bed. Then sit on the edge of the bed. When you feel able to do so safely, slowly stand up and start moving around. Have a light breakfast and drink lots of fluids. If you’re in pain, ask your nurse for more painkillers.

Surgical incisions

You will have between two and five small incisions on different parts of your abdomen. Each incision will be between 0.5 cm and 1 cm long. Stitches and/or surgical glue are used to close these surgical incisions, and any stitches used do not require removal and will slowly dissolve. Your surgical incisions may initially be covered with a dressing. You should be able to take this off about 24 hours after your operation and have a wash or shower (see section on washing

and showering). Any stitches in your front-hole will not need to be removed, as they are dissolvable. You may notice a stitch, or part of a stitch, coming away after a few days or maybe after a few weeks. This is normal and nothing to worry about.

One of your small incisions will be in your belly button area, so it’s important that your belly button is very clean before you attend hospital for surgery. When taking a shower, use a cotton ear bud to gently clean the belly button with water and your normal soap or shower gel. You must shower the night before and the morning of surgery.

Standard laparoscopy incisions Robotic assisted incisions

Anaesthetic effects

Modern anaesthetics are short lasting. You should not have any after-effects for more than a day after your operation. During the first 24 hours you may feel more sleepy than usual and your judgement may be impaired. You are likely to be in hospital during the first 24 hours but, if not, you should have an adult with you during this time and you should not drive or make any important decisions.

Bleeding

You can expect to have some front-hole/vaginal bleeding for one to two weeks after your operation. This is like light menstrual bleeding and is red or brown in colour. Some people have little or no bleeding initially, and then have a sudden gush of old blood or fluid about 10 days later. This usually stops quickly. You should use sanitary towels rather than tampons as using tampons could increase the risk of infection.

Pain and discomfort

You can expect pain and discomfort in your lower abdomen for at least the first few days after your operation. You may also have some pain in your shoulder. This is a common side effect of laparoscopic surgery. It normally settles after 48 hours. When leaving hospital, you should be provided with painkillers for the pain you are experiencing. Sometimes painkillers that contain codeine or dihydrocodeine can make you sleepy, nauseated and constipated. If you do need to take these medications, try to eat extra fruit and fibre to reduce the chances of

becoming constipated. Taking painkillers as prescribed to reduce your pain will enable you to get out of bed sooner, stand up straight and move around - all of which will speed up your recovery and help to prevent the formation of blood clots in your legs or your lungs.

Trapped wind

Following your operation your bowel may temporarily slow down, causing air or ‘wind’ to be trapped. This can cause some pain or discomfort until it is passed. Getting out of bed and walking around will help. Peppermint water may also ease your discomfort. Once your bowels start to move, the trapped wind will ease.

Starting to eat and drink

After your operation, you may have a drip in your arm to provide you with fluids. When you are able to drink again, the drip will be removed. You will be offered a drink of water or cup of tea and something light to eat. If you are not hungry initially, you should drink fluid. Try eating something later on. Once you’ve passed wind after the operation, you can go back to a normal diet.

Washing and showering

You should be able to have a shower or bath and remove any dressings the morning after your operation. Don’t worry about getting your scars wet – just ensure that you pat them dry with clean disposable tissues or let them dry in the air. Keeping scars clean and dry helps healing.

Blood clots

There is a small risk of blood clots forming in the veins in your legs and pelvis (deep vein thrombosis) after any operation. These clots can travel to the lungs (pulmonary embolism), which could be serious.

You can reduce the risk of clots by:

- being as mobile as you can as early as you can after your operation

- doing exercises when you are resting, for example:

- pump each foot up and down briskly for 30 seconds by moving your ankle

- move each foot in a circular motion for 30 seconds

- bend and straighten your legs - one leg at a time, three times for each leg.

Most people will be given Clexane injections for ten days after your surgery to reduce the risk of blood clots forming. Your nurse will show you how to give yourself this injection when you go home. You’ll be given compression stockings (‘TEDS’) to wear during your stay in hospital.

Cervical smears

Most people can stop cervical smear tests after hysterectomy if your last cervical smear test was normal or you’ve never been sexually active before. If you have had abnormal smear tests before, discuss with your surgeon whether you should stop.

Hormones and T

You can continue your testosterone if you are taking it throughout the journey through surgery. If you’re taking topical estrogen in the front hole (e.g. Vagifem or Ovestin) you can restart six weeks after surgery. If you’re taking other forms of HRT except T it’s important to discuss this with your surgeon at your initial consultation as you may need to stop.

Tiredness and feeling emotional

You may feel much more tired than usual after your operation as your body is using a lot of energy to heal itself. You may need to take a nap during the day for the first few days. A hysterectomy can also be emotionally stressful and many people feel tearful and emotional at first - when you are tired, these feelings can seem worse. For many people this is the last symptom to improve. If your mood is really affected, it’s important to seek help from friends, family or a medical professional.

What can help me recover?

Rest

Rest as much as you can for the first few days after you get home. It is important to relax, but avoid crossing your legs for too long when you are lying down. Rest does not mean doing nothing at all throughout the day, as it is important to start exercising and doing light activities around the house within the first few days.

A pelvic floor muscle exercise programme

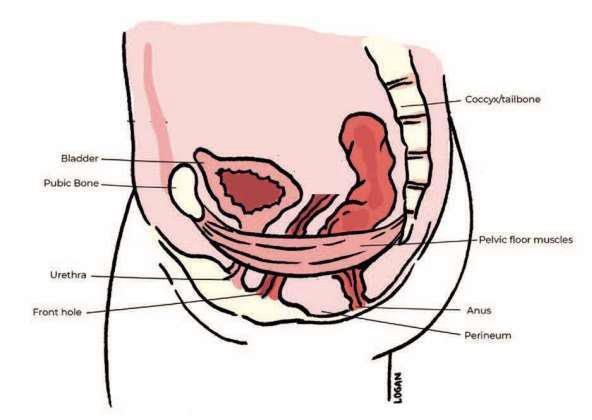

What are pelvic floor muscles?

Your pelvic floor muscles span the base of your pelvis. They work to keep your pelvic organs in the correct position (prevent prolapse), tightly close your bladder and bowel (stop urinary or anal incontinence) and improve sexual satisfaction if you use your front-hole. It is important for you to get these muscles working properly after your operation, even though you have internal stitches.

How to do pelvic floor exercises

To identify your pelvic floor muscles, imagine you are trying to stop yourself from passing wind, or you could think of yourself squeezing tightly inside your front-hole. When you do this you should feel your muscles ‘lift and squeeze’. It is important to breathe normally while you are doing pelvic floor muscle exercises. You may also feel some gentle tightening in your lower abdominal muscles. This is normal.

You can begin these exercises gently once your catheter has been removed (if present) and you are able to pass urine on your own. You need to practise short squeezes as well as long squeezes:

- short squeezes are when you tighten your pelvic floor muscles for one second, and then relax

- long squeezes are when you tighten your pelvic floor muscles, hold for several seconds, and then relax.

Start with what is comfortable and then gradually increase, aiming for 10 long squeezes, up to 10 seconds each, followed by 10 short squeezes. You should do pelvic floor muscle exercises at least three times a day. At first you may find it easier to do them when you are lying down or sitting. As your muscles improve, aim to do your exercises when you are standing up. It is very important to tighten your pelvic floor muscles before you do anything that may put them under pressure, such as lifting, coughing or sneezing.

Make these exercises part of your daily routine for the rest of your life. Some people use triggers to remind themselves such as, brushing their teeth, washing up or commercial breaks on television. Straining to empty your bowels (constipation) may also weaken your pelvic floor muscles and should be avoided. If you suffer from constipation or you find the pelvic floor muscle exercises difficult, you may benefit from seeing a specialist pelvic health physiotherapist.

A daily routine

Establish a daily routine and keep it up. For example, try to get up at your usual time, have a wash and get dressed, move about and so on. Sleeping in and staying in bed can make you feel depressed. Try to complete your routine and rest later if you need to.

Eat a healthy balanced diet

Ensure that your body has all the nutrients it needs by eating a healthy balanced diet. A healthy diet is a high-fibre diet (fruit, vegetables, wholegrain bread and cereal) with up to two litres per day of fluid intake, mainly water. Remember to eat at least five portions of fruit and vegetables each day! As long as you are exercising enough and don’t eat more than you need to, you don’t need to worry about gaining weight.

Keep your bowels working

Your bowels may take time to return to normal after your operation. Your motions should be soft and easy to pass. You may initially need to take laxatives to avoid straining and constipation. You may find it more comfortable to hold your abdomen (provide support) the first one or two times your bowels move.

If you do have problems opening your bowels, it may help to place a small footstool under your feet when you are sitting on the toilet so that your knees are higher than your hips. If possible, lean forward and rest your arms on top of your legs to avoid straining.

Stop smoking

Stopping smoking will benefit your health in all sorts of ways, such as lessening the risk of a wound infection or chest problems after your anaesthetic. By not smoking – even if it is just while you are recovering - you will bring immediate benefits to your health. If you are unable to stop smoking before your operation, you may need to bring nicotine replacements for use during your hospital stay. You will not be able to smoke in hospital. If you would like information about a smoking cessation clinic in your area, speak with the nurse in your GP surgery.

Support from your family and friends

You may be offered support from your family and friends in lots of different ways. It could be practical support with things such as shopping, housework or preparing meals. Most people are only too happy to help - even if it means you having to ask them! Having company when you are recovering gives you a chance to say how you are feeling after your operation and can help to lift your mood. If you live alone, plan in advance to have someone stay with you for the first few days when you are at home.

A positive outlook

Your attitude towards how you are recovering is an important factor in determining how your body heals and how you feel in yourself. You may want to use your recovery time as a chance to make some longer term positive lifestyle choices such as:

- starting to exercise regularly if you are not doing so already and gradually building up the levels of exercise that you take

- eating a healthy diet - if you are overweight, it is best to eat healthily without trying to lose weight for the first couple of weeks after the operation; after that, you may want to lose weight by combining a healthy diet with exercise.

Whatever your situation and however you are feeling, try to continue to do the things that are helpful to your long- term recovery.

What can slow down my recovery?

It can take longer to recover from a hysterectomy if:

- you had health problems before your operation; for example, people with diabetes

- may heal more slowly and may be more prone to infection

- you smoke - smokers are at increased risk of getting a chest

- or wound infection during their recovery, and smoking can delay the healing process

- you were overweight at the time of your operation - if you are overweight, it can take

- longer to recover from the effects of the anaesthetic and there is a higher risk of

- complications such as infection and thrombosis

- there were any complications during your operation.

Recovering after an operation is a very personal experience. If you are following all the advice that you have been given but do not think that you are at the stage you ought to be, talk with your GP.

When should I seek medical advice after a hysterectomy?

While most people recover well after a laparoscopic hysterectomy, complications can occur - as with any operation. You should seek medical advice from your GP, the hospital where you had your operation, NHS 111 or NHS 24 if you experience:

- Burning and stinging when you pass urine or pass urine frequently: This may be due to a urine infection. Treatment is with a course of antibiotics.

- Vaginal bleeding that becomes heavy or smelly: If you are also feeling unwell and have a temperature (fever), this may be due to an infection or a small collection of blood at the top of the front-hole called a vault haematoma. Treatment is usually with a course of antibiotics.

Occasionally, you may need to be admitted to hospital for the antibiotics to be administered intravenously (into a vein). Rarely, this blood may need to be drained.

- Red and painful skin around your scars: This may be due to a wound infection. Treatment is with a course of antibiotics.

- Increasing abdominal pain: If you also have a temperature (fever), have lost your appetite and are vomiting, this may be due to damage to your bowel or bladder, in which case you will need to be admitted to hospital.

- A painful, red, swollen, hot leg or difficulty bearing weight on your legs: This may be due to a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). If you have shortness of breath or chest pain or cough ,up blood, it could be a sign that a blood clot has travelled to the lungs (pulmonary embolism). If you have these symptoms, you should seek medical help Immediately

Getting back to normal

Around the house

While it is important to take enough rest, you should start some of your normal daily activities when you get home and build up slowly. You will find you are able to do more as the days and weeks pass. If you feel pain, you should try doing a little less for another few days.

It is helpful to break jobs up into smaller parts, such as ironing a couple of items of clothing at a time, and to take rests regularly. You can also try sitting down while preparing food or sorting laundry. For the first one to two weeks, you should restrict lifting to light loads such as a one litre bottle of water, kettles or small saucepans. You should not lift heavy objects such as full shopping bags or children, or do any strenuous housework such as vacuuming until three to four weeks after your operation as this may affect how you heal internally. Try getting down to your children rather than lifting them up to you. Remember to lift correctly

by having your feet slightly apart, bending your knees, keeping your back straight and bracing (tightening or strengthening) your pelvic floor and stomach muscles as you lift. Hold the object close to you and lift by straightening your knees.

Exercise

While everyone will recover at a different rate, there is no reason why you should not start walking on the day you return home. You should be able to increase your activity levels quite rapidly over the first few weeks. There is no evidence that normal physical activity levels are in any way harmful and a regular and gradual build-up of activity will assist your recovery. If you are unsure, start with short steady walks close to your home a couple of times a day for the first few days. When this is comfortable, you can gradually increase the time while walking at a relaxed steady pace. Many people should be able to walk for 30- 60 minutes after two or

three weeks. Swimming is an ideal exercise that can usually be resumed within two to three weeks provided that vaginal bleeding and discharge has stopped. If you build up gradually, the majority of people should be back to previous activity levels within four to six weeks. Contact sports and power sports should be avoided for at least six weeks, although this will depend on your level of fitness before surgery.

Driving

You should not drive for 24 hours after a general anaesthetic. Each insurance company will have its own conditions for when you are insured to start driving again. Check your policy.

Before you recommence driving you should ensure that you are:

- able to make an emergency stop

- able to comfortably look over your shoulder to manoeuvre.

Before you drive you should be:

- free from the sedative effects of any painkillers

- able to sit in the car comfortably and work the controls

- able to wear the seatbelt comfortably

In general, it can take two to four weeks before you are able to do all of the above. It is a good idea to practise without the keys in the ignition. See whether you can do the movements you would need for an emergency stop and a three-point turn without causing yourself any discomfort or pain. When you are ready to start driving again, build up gradually, starting with a short journey.

Travel plans

If you are considering travelling during your recovery, it is helpful to think about:

- the length of your journey - journeys over four hours where you are not able to move around (in a car, coach, train or plane) can increase your risk of deep vein thrombosis (DVT);

- this is especially so if you are travelling soon after your operation

- how comfortable you will be during your journey, particularly if you are wearing a seatbelt

- regarding overseas travel:

- would you have access to appropriate medical advice at your destination if you were to have a problem after your operation?

- does your travel insurance cover any necessary medical treatment in the event of a problem after your operation?

- whether your plans are in line with the levels of activity recommended in this information.

If you have concerns about your travel plans, it is important to discuss these with your GP or the hospital where you have your operation before travelling.

Having sex

You should usually allow four to six weeks after your operation to allow your scars to heal. It is then safe to have sex as long as you feel comfortable. If you experience any discomfort or dryness you may wish to try a vaginal lubricant. You can buy this from your local pharmacy.

Returning to work

Everyone recovers at a different rate, so when you are ready to return to work will depend on the type of work you do, the number of hours and how you get to and from work.

You may experience more tiredness than normal after any operation, so your return to work should be like your return to physical activity, with a gradual increase in the hours and activities at work. If you have an occupational health department, they will advise on this.

Some people are fit to work after two to three weeks and will not be harmed by this if there are no complications from surgery.

Many people are able to go back to normal work after three to six weeks if they have been building up their levels of physical activity at home. Returning to work can help your recovery by getting you back into your normal routine again. Some people who are off work for longer periods start to feel isolated and depressed.

You do not have to be symptom free before you go back to work. It is normal to have some discomfort as you are adjusting to working life. It might be possible for you to return to work by doing shorter hours or lighter duties and build up gradually over a period of time.

Consider starting partway through your normal working week so you have a planned break quite soon. You might also wish to see your GP or your occupational health department before you go back and do certain jobs - discuss this with them before your operation. You should not feel pressured by family, friends or your employer to return to work before you feel ready. You do not need your GP’s permission to go back to work. The decision is yours.

Your surgical plan

| Week before surgery | You may need to attend hospital for your pre-operative assessment and tests. You will be contacted if this is the case.

|

| Night before surgery |

|

| Morning of surgery |

|

| Immediately after surgery (in the recovery room) |

|

| Back on the ward (1–2 hours) |

|

| Back on the ward (2–4 hours) |

|

| Back on the ward (after 4 hours) |

|

Recovery tracker

| Time after operation | How might I feel? | What is safe to do? | Fit to work? |

| 1–2 days |

|

|

No |

| 3–7 days |

|

|

No |

| 1–2 weeks |

|

|

Maybe |

| 2–4 weeks |

|

|

Yes |

| 4–6 weeks |

|

|

Yes—if you do not feel ready to go back to work please discuss this with your GP |